Learning

Restorative Practice

Part 1: Building Relationships

Relationships between the students are critical, as is the relationship between the students and the teacher. When relationships are ‘right’, each person has a voice. Mutual respect exists. Teachers spend time each week in discussion with students about how their words and actions affect other people.

Teachers use circle activities to build relationships and give every student a voice. Sometimes students meet in circles to play games. At other times, circles are a way of conducting classroom discussions so that each child has a turn to share his or her views on an issue. Bullying cannot emerge in a community of people that respect and care for one another. In an ideal world, the effort we put into building relationships prevents rude, mean and bullying behaviours from occurring.

Part 2: Telling the Story

Unfortunately, we don’t live in an ideal world. Hence, relationships between people will be broken by rude, mean or bullying behaviours. When those antisocial behaviours happen, we help students tell the story.

Children often come to parents or other adults, pointing fingers and saying, “He/she [name the action].” When they do this, one or more of the following things are true:

- They are feeling hurt

- They see only the end of the story

- They are afraid of getting in trouble

- They believe that the person who started it is the one who should get in trouble

The first step in fixing a problem is helping students tell the story from beginning to end, saying something like, “Let’s go back to where this all began…” Our goal is to help students identify the thoughts and feelings associated with the actions at the beginning, middle and end. Once the story has those three parts, students generally agree that both people made choices that contributed to the problem in some way (even though the contributions were not necessarily equal in intensity). For example, the problem may have started when one person felt excluded from a game or thought that someone was trying to ‘steal’ a friend.

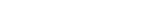

Part 3: Justice should heal

In this third part, we trace back over the story with the students, asking each person what they were thinking and feeling at each part of the story. We ask about who has been harmed beyond the students. The other person? The class? Younger students who saw the incident? Parents who were worried? This ensures two things:

- Each party has a voice

- The harm has been explored from multiple angles

At this point, students often see that a simple “I’m sorry” doesn’t always take away the pain that others have experienced. Repair may take time. Healing begins when victims hear true remorse from the one(s) who hurt them.

Part 4: Plans are put in place and Consequences are agreed

Even when students agree that each person was responsible for antisocial choices, they are not necessarily equally responsible. The actions are underpinned by thoughts and feelings that have a range of consequences.

In this final step, we ask the students what might be done to fix the problem. What is fair? When we were in school, school officials assigned punishments to behaviours. Those punishments usually did nothing to repair the damage done. In a Restorative Practice context, consequences should be SMART: Specific to the behaviours, Reasonable, Sensible, Valuable, Practical. We work with the students and families rather than doing things to the students. The consequences hold all parties accountable for their actions and help build social-emotional skills.

In the case of physical violence, some form of suspension is likely to be a consequence for the person(s) that caused physical harm. The purpose of the suspension is to allow for cool-down time. While the suspension is happening, the person(s) responsible for the physical violence spends time reflecting on the behaviour triggers, talking about how those triggers might be better dealt with in the future, and ways that the those who experienced or witnessed the event can feel safe at school.

Not every situation results in Restorative Practice

The best outcomes happen when students who have done the wrong thing immediately admit it and openly discuss ways in which the situation can be fixed. Our goal is that students understand how their behaviours have affected others and show genuine interest in resolving issues.

The Restorative process breaks down if the people who have caused harm do not admit their part in the harm. The person who feels victimised continues to live in fear of harm or retribution. If this is the case, the Coordinator or Head of School may need to move into an investigation and take a punitive approach. The antisocial behaviours may result in multiple-day internal or external suspensions from school.

You can help

If your child comes home upset by something that has happened at school, you can help us in the restorative process. Empathy and sadness for your child will likely be the first reaction – and will help your child begin to heal.

As much as possible, help them tell the story from beginning to end. Questions that begin with where, when, how and what help your child re-tell the story (why questions are harder). Focus on the events of that particular day.

Let the teacher know your child’s version of the story from beginning to end. Do this the first day – the longer you wait, the more difficult it is for the teacher to investigate. Please do not wait and tell the teacher “This has been happening for weeks/months/years” – teachers can’t realistically fix things that happened a long time ago. They can, however, investigate something that happened in the past 24 hours.

Realise that there may be other explanations for the behaviours that hurt your child – not because your child is lying – because the ability to see issues from multiple perspectives is developmental.

Please avoid words like “bully” or “naughty child” or other behaviour labels when referring to other children. In Romans 3:23, the apostle Paul is clear that “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.” Consider how you’d feel if those words were stated about your child.

Share the issues with the teacher and think carefully before sharing the situation with other parents. There is often a fine line between seeking support and gossip – a line that only your conscience can judge. Psalm 19:14 states, “May these words of my mouth and this meditation of my heart be pleasing in your sight, Lord, my Rock and my Redeemer.” We hope you will model the values of compassion when speaking about students – all of whom have life lessons to learn.